Interview with Journalist & Author: Eva Giovannini

This interview appears in the January 2021 Issue of The Open Doors Review. To view the magazine, click here.

To view the Italian transcript and original audio in Italian, click here.

Introduction

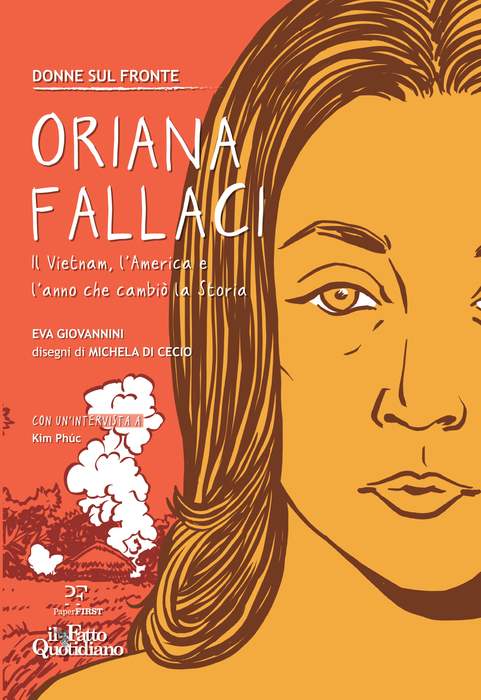

Eva Giovannini is the author of the Graphic Novel Oriana Fallaci: Il Vietnam, L’America e l’anno che cambiò la Storia. It’s part of a series called “Donne sul Fronte” (Women on the Frontlines), the first large series of graphic journalism published in Italy by PaperFirst and the newspaper Il Fatto Quotidiano. The series of seven volumes puts women at the center of a journalistic work in which journalists tell either the stories of previous war reporters or recount direct experiences from their own reporting.

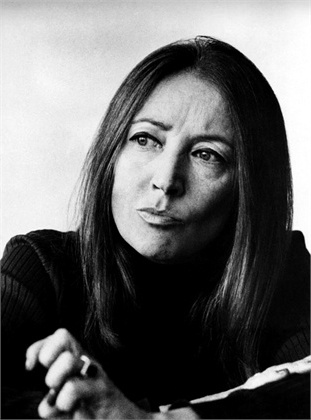

The first volume, written by Eva Giovannini is dedicated to Oriana Fallaci, the internationally famous Italian journalist who, in addition to being a war reporter at a time when women were almost never considered for such roles, became known for her fearsome political interviews with such figures as Yasser Arafat, Indira Gandhi, Ayatollah Khomeini, Muammar Gaddafi and Deng Xiaoping among others. Of his interview with Fallaci Henry Kissinger admitted it was a desastrous decision after she got him to admit that Vietnam was a “useless war.”

Eva Giovannini is an Italian journalist, born in Livorno. Reporter for RAI, the author of the book: Europa Anno Zero: il Ritorno dei Nazionalismi, she has also been the presenter of two editions of Italy’s famed Premio Strega prize ceremony and the winner of the Altiero Spinelli Journalistic Prize for European studies. Oriana Fallaci is her first Graphic Novel.

Interview (translated into English)

Lauren: Could you describe Oriana Fallaci to someone who might not have heard of her?

Eva: Oriana Fallaci was the most important female Italian journalist in the world. Today she remains the most famous journalists that Italy has ever had. She was the first journalist from our country sent to war and the only female Italian journalist sent to Vietnam. Oriana Fallaci had an enormous international fame. Her books were published in 30 languages. All of them have been translated in English. She lived for part of her life in New York on the Upper East Side. She had a very difficult childhood because she was born on the eve of the second world war and along with her family she was a partisan, meaning they fought against the Nazi Fascists. This experience influenced her entire life. She was always deeply libertarian, some would say anarchist, certainly anti-fascist but never communist. Unfortunately, in the last years of her life, her fame was linked to her last works that were pub-lished after September 11 (she died in 2006). In the last five years of her life she wrote terrible things about Islam, very intense and virulent things that she has been strongly criticized for. I also did not share her opinions on her last works … more than anyone else, the Left ripped her apart. This is why the Italian Right have since appropriated her name but I think if Oriana Fallaci knew that Matteo Salvini had gone to place a flower on her grave to make her a symbol for his party, she would be incredibly angered by that.

Lauren: She was indeed very criticized for her opinions on the Islamic world. Considering todays tendency toward “cancel culture,” many have written off her work. Do you feel it’s necessary to justify what she wrote at the end of her life or is possible to focus simply on one part of her life?

Eva: In my opinion it would be very wrong to reduce Oriana’s work to the last years of her life. She wrote many intense things but they are just one part of her journalistic and literary works. She wrote many books that are extraordinarily beautiful and that changed the very idea of what Italian journalism could be, especially female Italian journalism. She was a pioneer from any point of view. Books like “A Man” or “Nothing and Amen” or “If the Sun Dies” … these books are immortal.

Lauren: Why did you choose to focus the Graphic Novel on this particular period of her life – the first years she was in Vietnam?

Eva: I was asked to choose a period from Oriana’s life that would represent one of her wars. I could have chosen the final part of her life which she described as the war against “the alien” which was the tumor that eventually killed her. But I chose Vietnam because it seemed like such an interesting and exciting part of her professional life. She was already very famous but not super famous. She was at the dawn of global fame when she left for Vietnam. In fact, “Nothing and Amen,” her book about Vietnam that came out in ’69 would have an incredible success and be translated all over the world. I chose Vietnam because in those years, Oriana wasn’t the only one experiencing fundamental changes. It was the first really important war she followed, but America was also changing. There were the university protests in ’68, man on the moon, the assassinations of Bob Kennedy and Martin Luther King. Oriana went back and forth between Vietnam and the United States, reporting on these two fronts that were very different but incredibly interesting. So, it seemed like a period in which many things happened and from which everything changed.

Lauren: Donne sul front is a project in which Italian female journalists, document other female journalist – why do you think this is an important project?

Eva: I didn’t choose this connection. The idea came from Luigi Politano, the editor of Round Robin who had the insight to have female journalists writing about other female journalists. I think that it’s importnat for women to not always write about the “women’s issues” but to write about the whole world. Too often, in our papers, women’s names come up when the subject is babies or discrimination or the victims of femicide. I want to find wom-en’s names associated with stories about Iraq, Siria, Libia, international tensions, Covid… I want to find women’s names associated with world-relevant topics not just “women’s topics.” That’s what makes a real difference.

Lauren: Fallaci wrote about some of these “soft” maybe more “female” topics like the life of Hollywood actors but also about war and she became known for some incredible interviews with powerful leaders around the world. Considering your personal experience today, do you think female journalists have more opportunities to write about any argument or are they too often relegated to these “female” topics?

Eva: The road is still long, but there’s no doubt that there has been enormous progress in comparison to the ‘70s when Oriana wrote for l’Europeo, the paper where she was the only woman to appear on many topics. In those years there were only two or three female journalists in Italy who wrote about politics. She was the only one to go to the frontlines. Today no. Today, we are many, we write about everything, we report on wars… I personally have worked for many years in international politics, following European issues and extreme right terrorism. I can’t say I have ever been discriminated for my sex.

Lauren: What was your personal path to enter the world of Journalism?

Eva: I graduated in Pisa with a degree in international literature and then I did two years of journalism school in Rome, after which I did an internship and then I got some contracts with Sky TG 24. From there, I really began. I did a very standard path because I worked in Livorno with the daily il Tirreno, but let’s say that the jump to national work was possible through the journalism school that gave me the opportunity to become a professional journalist.

Lauren: So you always wanted to do this work? Since you were very young?

Eva: Yes, since I was little, I have to say I was very curious and I loved words. I was extremely curious about many different things. In 1989, when the Berlin wall fell I was 9 years old and I remember watching the live coverage by RAI with Lilli Gruber, the journalist in Berlin speaking about how the wall fell… and I remember thinking, this is the most amazing job in the world.

Lauren: Was Fallaci a point of reference for you as you became a journalist yourself?

Eva: Yes, she was an unreachable model. A true “Maestra” with a capital M. In my parents house we had “A man” and “Letter to a child never born,” which is a masterpiece, and I thought basically that she was just untouchable. Then when I was older, after September 11, I was 20 years old and I criticized her a lot. But I never lost sight of the fact that people are never one thing, they are always many things and should be viewed in their entirety.

Lauren: I’ve been reading a biography of Fallaci’s life and I noticed that the details included in the Graphic Novel are very accurate down to the dialogue and specific events. Was this project the work of biography or did you fictionalize anything?

Eva: No, I kept very faithfully to reality. I really just had to work on making cuts so in that sense, I took the liberty of choosing which things would be included but I didn’t invent anything. I studied a lot and didn’t invent anything.

Lauren: How was the experience over all of creating a Graphic Novel?

Eva: Fun. Tiring, because of all the revisions – I did ten drafts. Fascinating, because I learned how to make a Graphic Novel from research right up to designing the vignettes, like the process of saying, “Ok, I’m going to tell this episode” – that’s already a choice… but then, What do I tell exactly? Everything? No. Because the vignette has to say everything in ten words so… ok… how do I arrange the scene? Whose point of view is it from? Are we seeing through Oriana’s eyes or someone else looking at Oriana? Is the scene seen from above or below? Is this panel silent or do we have her say this line here or do we keep it from the next panel? These kind of questions… for 67 pages.

Lauren: The story you included of Oriana’s attempt to adopt a child in Vietnam really struck a cord with me. Why did you choose to include this detail to illuminate her character out of all the years she was in the war?

Eva: Because in the book “Nothing and Amen,” she wrote about this story in a way that was masterful and that really hit me. And also because I think it was an episode that changed the course of her life – she was 38, 39 years old, she wanted to be a mother, she was in love with François Pelou but he was married. Their love story lasted many years but they never had children. She says at one point that she has a strong need for life and decides, “Ok, I’ll adopt a child.” Then she had the great misfortune to not be able to do it because the girl she chose turned out to be blind, they wouldn’t let her adopt her, there were complications. Then Oriana never got pregnant, well, she did but she lost the children through miscarraiges. Who knows what would have happened in Oriana’s life if she could have brought home that Vietnamese child and become a mother. Who knows if the path of her life would have been the same? We can’t say but I’ve always been fascinated with these turning points. Those moments in which anything can happen and can change the direction of your life and you’ll never know if it was destiny that something didn’t go as you wanted or because you made a mistake.

Lauren: Oriana argued with an editor at the beginning of her career because she didn’t want to write an article with the explicit angle of the newspaper. For her, uncovering the truth about a person or situation is always the most important thing. At the same time, she said that a journalist can never be completely objective, that you can never fully separate yourself from your work. What do you think about that?

Eva: She was a free journalist, first of all. Free, very prepared, she studied a lot and she was never detatched from the things she wrote about. That doesn’t mean she wasn’t intellectually honest, she was intellectually honest, but she had a bias, in the sense that in every situation she had her opinions. She said that so-called Anglo-Saxon journalism, or journalism that didn’t take a position didn’t exist in her opinion. Because we all have a filter that is cultural, or emotional or biological or familial, that influences our point of view. What is the difference between a deceptive or manipulative journalist and Oriana Fallaci? It’s that Oriana Fallaci declared that she had a point of view. She didn’t pretend not to have one. She declared it. And this was what made her great because she was always as sharp as a knife but she didn’t take orders from anyone. Her point of view was hers, never of whoever commissioned her to do an interview, it was always just Oriana.

Lauren: Could you recommend a book of Oriana’s?

Eva: I’d recommend “Nothing and Amen” because its as the source of inspiration for this project.

“Oriana Fallaci: Il Vietnam, L’America e l’anno che cambiò la Storia” by Eva Giovannini and the other volumes of “Donne Sul Fronte” are available for puchase online at shop.ilfattoquotidiano.it.